I would like to share my life story in an effort to document the suffering of my family as a result of my grandfather’s military service and residency at Camp Lejeune, which we were completely unaware of until April 4th, 2024. This is a story of generational trauma, pain, anguish and ultimately understanding of history.

MOTHERED

My name is Jessica. I was born in 1978 in Bridgeport, CT to 19-year-old Jaimee Rohlfs. About 18 months after I was born, in May of 1980, my maternal grandfather passed away from an aggressive lung cancer that could not be explained by his medical team. His illness was short, and his death was swift. He was 41 years old and was survived by his wife and six children. My mother was pregnant and within weeks of delivery with my sister at the time. She was very close to her father and suffered greatly as a result of his death, both because of its sudden and unexplained nature, and also his relative youth being only 41. I was only 18 months old, so I never knew him, although my recent understanding from family members is that he was a Marine through and through, proud of his service and no nonsense.

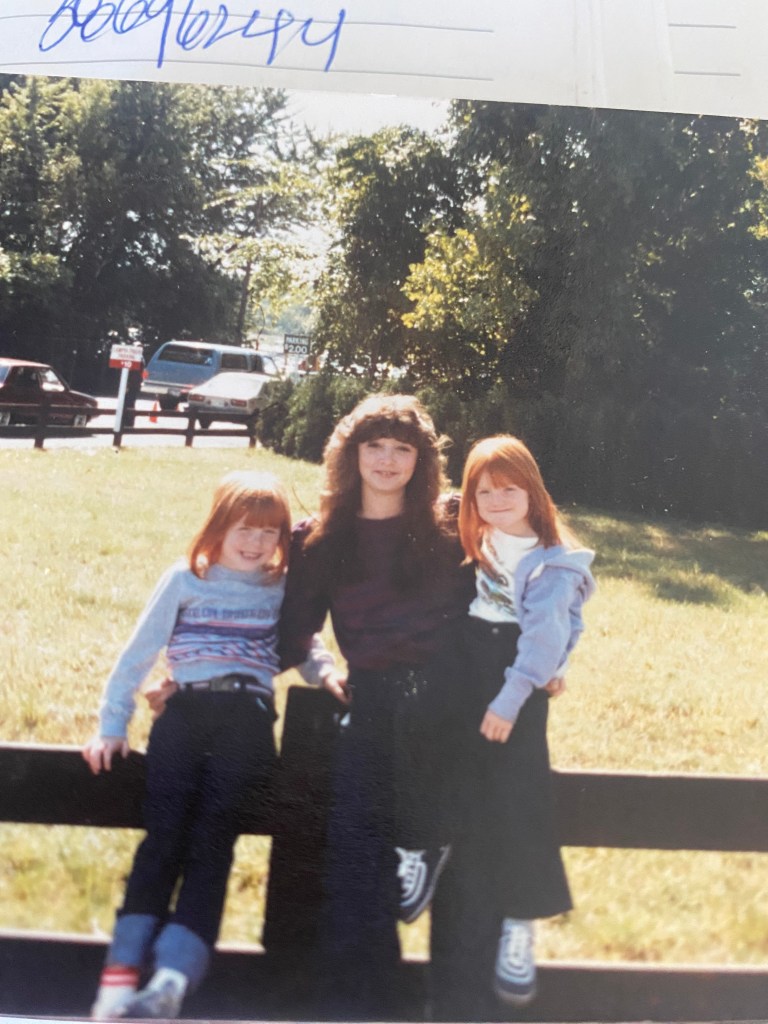

My maternal grandmother passed away in December of 1995, at age 57. In the preceding 15 years, her breast cancer was treated with Chemo, radiation, a double mastectomy and reconstruction, and ultimately, she succumbed to the illness. Obviously, this was a crushing blow to my mother at age 36 to become an orphan. She and her mother were close in spite of the distance between them with our family living in CT and my grandmother living in FL. We had done lots of visiting both with summers spent in FL with our grandmother and with her visiting the family in CT often. I am very thankful for that opportunity, and it is even more special to me in retrospect because it was an innocent time, not knowing she would be dead within a few years. I was 17 when she died and a senior in high school.

My mother was a vibrant, beautiful, lively woman who was universally adored for her striking beauty, her kindness, warmth, and her overall good nature. I remember when I was in high school the principal, Mr. Monroe, would be thrilled if I got into trouble at school because it meant he’d have an excuse to call my mother. She was a mentor to the young women in her department at the bank, a beloved aunt and friend, a foster parent, a stepmother, and my personal compass toward being the type of woman she would be proud of. She was truly like the sun, and I wanted to bask in her rays-I was crazy about my mother.

A special memory is when my mother made homemade Bert and Ernie cookies. I was probably three, and I thought who I was to be given this incredible treat. They were cutout cookies, with colored icing and googly eyes. The stuff of a three-year-old’s dreams. My mother was a god in my eyes then.

We lived in a small duplex in a neighborhood with lots of kids and our life then was pretty idyllic as I remember it. We had a foster brother, the same age as Meg at the time. My mother loved that kid so much. He ended up being adopted, but my mother never forgot him. I haven’t either.

My mother had not graduated high school because she decided to leave school and get married. She worked incredibly hard in her 20’s to obtain a GED, find a job, and work her way up to a VP position in a bank, all while raising four children. She was a well-respected employee, beloved at Chase Bank, where she ultimately landed in the ATM/EFT department. She truly was an inspiration in how she created the life she wanted, in spite of humble beginnings.

She had left her hectic job in 1996 to pursue a job where she could work from home and enjoy her home and children, after many years of the grind. It was the same year I went away to college. She moved our family to Watertown with her future husband. She loved decorating her home, gardening, cooking for her family, driving around to tag sales on Saturday mornings while listening to country music and singing along to Reba or Trisha Yearwood. The October before she died, she and I planted hundreds of bulbs around our yard, and I didn’t mind the yard work one bit because I got to spend the time with my mother talking and joking. She would call these days “yard work parties” to convince us it would be fun, but I needed no convincing. I felt like we were living our golden age during those years-my mother was so very happy and I loved my extra siblings, our new house and the direction our family was taking.

Fast forward to Christmas of 1998. We celebrated the holidays with our blended family, as our mother had married the previous New Years Eve, and we were now a family of 7 kids ranging in age from 24 all the way down to 13. My mother, age 39, began to experience cold-like symptoms in the days after Christmas and went to an urgent care MD who suggested she was suffering from a cold, and she was sent home.

Within days she was experiencing difficulty catching her breath and she reached a point where she was so afraid that she agreed to go to the emergency room. It took a few days for her to be diagnosed with Stage 4 Lung Cancer-Non Small Cell Adenocarcinoma. She truly never had a chance, and no treatment was offered other than measures to manage her symptoms and reduce the excruciating pain. She spent her final weeks first attempting to come home and use hospice services, but ultimately relenting and returning to the hospital for her final days. Her 40th and final birthday fell during the time she was home (January 17th) and we had a birthday party for her at the house. We all knew by then what was happening, although I think she tried to protect us as much as she could. It was the saddest birthday ever, as she sat in her hospital bed in our living room, opening gifts she wouldn’t live to use, her beautiful hair sheared off because it was near impossible to wash in a hospital bed, and she could no longer walk at all without losing her breath. Her eyes were sunken into her head, and she was using oxygen, and on a morphine drip.

My sister was attending her freshman year in college at the time, and I was tasked with calling her at school to let her know our mother would not survive. Even as I was saying it to her, I did not believe it. I had to make dozens of similar phone calls to far flung relatives and friends letting them know this horrible news to their shock, then to convince them that truly there was nothing anyone could do, and then to listen to them crying and attempt to comfort them. I was 20 years old and pregnant with my first child, attending community college and working.

My mom kept attempting to convince me that she would be around to meet my daughter, who was due in June of 1999. I think she was trying to be strong for me, knowing what she went through when her father died during her pregnancy. My pregnancy was unplanned, and my mother was my support through a difficult time-she promised to help me with my child before all of this. My plan was to stay home with her and my family and raise my child myself. She would tell all the doctors at the hospital who were treating her that I was carrying her grandbaby. As a kindness, my OBGyn, Dr. Vodra, and the nurses on my mother’s floor conspired to conduct my 20-week ultrasound in Waterbury Hospital, rather than the regular OB office. They wheeled my mother down in her hospital bed and she held my hand while we found out what “we” were having, whether it would be a boy or a girl. The technician printed photos for her, and we found out we were having a girl baby, which was my hope-I wished to be the type of mother to my child that my mother was to me. I had planned to name her Molly Cate and my mother made all the nurses and doctors ooh and ahhh over her grandchild. She hung the photos up in her room. It was a whole reel of them where they usually give you like 3 or 4. I will forever be grateful to those who planned that on our behalf. In retrospect, it was a weird crossover between life and death, which I think everyone in the room was acutely aware of, other than me. I remember her nurses were there and were tearing up. I still held out hope that this was all some kind of awful mix-up.

She had to endure so much testing and so many awful procedures to both keep her comfortable and hopefully extend her life, even minimally. I remember one particularly brutal procedure where a thick metal hollow rod was inserted through her back and then through her ribs and ultimately into her lung to drain the fluid that was building up. I was holding her hands as she was hunched over, and she was crying and trying so hard to stay still. She told me she was tired and wanted to give up. I knew she was tired and the life she was living was not what she wanted. I remember being grossed out by the contents of the drainage bag and feel such shame about my youthful idiocy-I was not thinking clearly. She would talk at times about looking forward to seeing my 2 cousins, Christopher and Charlie, who had passed away from Muscular Dystrophy, and her parents, whose absence was excruciating for her. I remember getting really pissed off and begging her not to do this to me and telling her that I could not handle her leaving me. She asked me to keep our family together and take care of my youngest sister, who had just turned 13 a few weeks prior.

During her hospital stay, she charmed the nurses at Waterbury Hospital, and they were gutted by what was happening to her. She was asked about toxins and contaminant exposure, because the MDs could not explain why this would be happening to her. Of course, she did not know much about her family history since both of her parents were dead and the idea of having been exposed in utero was not even brought up.

One night we had planned, at my mother’s behest, a little event at the hospital where we would watch “Dirty Dancing” while eating Jim Dandies, which were her favorite Friendly’s sundaes. Her best friend, my Aunt Charlene, came, along with Uncle Brian-they were very dear to her, despite divorcing Uncle Brian’s brother (my father who was absent from age 4 on). We watched the movie, laughed and enjoyed our ice creams-my mother was no longer eating at all by then, so she moved hers around with the spoon. I know she wanted to eat it, but just couldn’t which was super sad, and even in retrospect is an awful memory. I remember leaving that evening and kissing her on the forehead-she was often in and out of consciousness because of the morphine.

I went to my apartment and went to sleep. It was January 31, 1999. I was startled awake around 3 am. I felt the universe had shifted in some giant way and when the phone rang 2 minutes later, I knew what it was about. I don’t even remember who called me, but I remember the helpless feeling of having literally nothing to do. What do you do? Go back to sleep? I screamed a guttural scream and sobbed and cursed God for taking her. I was on my knees literally feeling as if I would die too, and that it would be a mercy.

The following days are a blur of funeral planning and tears and attempting to adjust to this unexpected but monumental change in our family, which was new. I remember trying to choose songs for her funeral and thinking what the hell is this? How do you choose and who even cares? Nothing mattered at that time except the gigantic empty hole in my soul. It was early February. I chose clothes for her for the open casket-a summer dress I always loved on her, and I brought her make up to the funeral home along with a photo of how she typically looked to work from. I had forgotten that there was nail polish in the make up bag. When we went to the wake, I saw the funeral home staff had painted her nails with the saccharine pink nail polish. How could I have done something so stupid? I don’t know why the nail polish was even in the bag in the first place, but my mother was not someone who painted her nails. Ugh. The image of her with a short bob, her nails painted a garish color, an empty shell of my mother, who had always embodied safety, love and light is forever seared into my mind.

We chose a cemetery in our town, and she was buried in a new section overlooking the grounds of a private school next to a bucolic field, the first burial there-I remember thinking it would be lonely. And I remember agonizing over leaving the funeral at the cemetery because I would never be close to her ever again as long as I was alive. Later it also occurred to me that a summer dress was grossly inadequate for a New England winter, and I cried about the poor choice I had made for her. I felt like an awful daughter who couldn’t even get that right. I was so young.

MOTHERLESS

I do not remember the rest of my pregnancy at all. I know my Aunt Charlene and my mom’s friend Peg planned a baby shower for me, but I don’t remember one minute of it. I even married the man whose child I was carrying because what else was I going to do? Don’t really remember much of that either. I was so incredibly traumatized that most of the next 5 years are absent from my mind.

My daughter was born the weekend after Mother’s Day that year. She was born early but was healthy and beautiful. We ended up naming her Maia, because saying the name my mom and I had chosen would be a painful daily reminder of what was lost.

I had no choice but to be Maia’s mother, so I jumped into trying to be the best mother I could be, although it was extremely difficult to be both dealing with a loss, and a new marriage, and I know I could have done better in a lot of respects if I had family support.

I went on to also have a son, Hani in October of 2002. I was a stay-at-home mom to my kids, a choice I made because I was afraid to miss anything. When Hani was about 6 months old, I took him outside to take some photos. The sunlight hitting his head caught the little hairs on his head and I could see a shimmer of red! My mother would have loved to have another little redhead in the family.

With the early deaths of my maternal line relatives, I began to believe that the same fate would befall me. It was suggested by well-meaning relatives that because her father had died of the same cancer, perhaps there was a genetic component to it. I talked to my doctors over the years, and they were dismissive of the idea, but I always truly believed it was inside me like a ticking time bomb. I had a hard stop date for living in my mind. I calculated the exact date I would be the same age as my mother at her death (40 and 2 weeks) and had that in my mind as my “drop dead” date, September 19, 2018. To further my fears, I had done some youthful smoking, so I figured if I got lung cancer, I could only blame myself, and it was destiny anyway.

With these fears in mind, I spent my life never truly allowing anyone to know me. I hesitated to share my history with people who didn’t already know. I have thought a lot about this recently and I think it was because when I would meet someone new, I knew they would ask where I was from, and the follow up question “where do your parents live?” and then I would tell them something that would make them feel bad and also allow them to know that I was a defective person, unworthy of having a mother or an extended family. At the young age of my loss, none of my peers had experienced this type of loss, and in fact most of my friends still have both of their parents to this day. I think they did not want to talk about the subject because perhaps they feared it could be contagious. In this way, I did not have a lot of support, because there weren’t many who could understand the magnitude and gravity of this loss, and they did not want to. I did not want them to truly understand either. I remember telling a friend a couple of years earlier that losing my mother would be the most devastating thing that could happen to me.

I have felt like I am not a normal full person, or a person who deserves a family. I feel that I brought my kids into the world to this empty existence devoid of regular holidays and celebrations. My children have never had a grandparent from my side at a single birthday party. What they did have was fear-which is both my fault and the fault of the Marine Corps. They lived with the idea that my life would be short, because that seemed to be a foregone conclusion. If the medical community couldn’t even tell me why this happened to my mother and grandfather, how could they prevent it from happening to me too?

With that in mind, I parented in a way that I felt would best prepare my children for my early death. I would regularly take a mental accounting of how they would fare if I suddenly died in 4 or 5 weeks(since that’s how long my mom and grandfather had from symptom to death). Each milestone did not feel like a moment of pride for me, but rather a relief that my kids would remember I was there for it, when I ultimately died. I wanted them to be independent and have the skills to make it in the world without me. I never considered for a second that I would see my daughter graduate from college or get married. I have been somewhat standoffish with love and affection, because I thought it would ultimately hurt my children less when I died. That is a heavy emotional burden to carry-it is a combination of guilt, fear, and a heart wrenching resignation.

Despite my promise to my mother, our family did not stay together. In recent reflection, I’ve surmised that it is difficult to connect when your history is a legacy of shared pain, sadness, death and loss. My sisters reminded me of the before-family holidays, making cookies with my mother, singing along to the Carpenters Holiday Album on CD, which had a skip on one particular song, and we would continue singing the skip over and over before we’d shake the player, raucous laughter filling the air. They reminded me of family trips to Disney and New Hampshire to stay the lake house. All of that became too painful to even think about. I had a mentality of just moving forward and not perseverating on things that could not be changed.

My holidays have primarily been spent with friends or partners families. I have always felt that I’ve invaded other people’s holidays and that I was an observer or a “third wheel” or that people just felt sorry for the “poor orphan girl”, almost as if people were earning karmic points by including me. It’s been a source of shame for me, so much so that it has been hard to enjoy a holiday wholeheartedly. I do wish to acknowledge my Aunt Charlene and Uncle Brian here. Aunt Charlene promised my mother that she would take care of us, in exchange for my mom taking care of Aunt Charlene’s three deceased children on the other side. What a bargain to make! My Aunt has very much honored her promise. She was the first person to come help me when my daughter was born, and she would come help me absolutely any time I needed her to. They treated my children as if they were their grandchildren, indulging them with holiday gifts, generous contributions toward their college tuition, vacations, and so much love. What is complicated about that is that every occasion feels haunted on both sides by the specter of the people who are absent.

Over the years, friends and family have noted my resemblance to my mother. I found these comparisons sad and terrifying. I rejected the idea of being like my mother, because to me, that meant an early and awful death. I tried to rail against anything that made me like her. My Uncle Brian has often said when I cook or clean, my movements remind him of her-but of course they do because she taught me to cook over years of assisting her with family dinners. But I rejected my mother and her memory many times because of fear. I could not think about her without thinking about my relationship to the bad thing that killed her. With that in mind, I spent a lot of time minimizing her role in my life and my loss. I was not like her. I often would look for ways to convince myself that I was more genetically like my father’s family. If I had the same wide back as my uncle, maybe I was healthier and had better genetics than my maternal family. I have such guilt for putting my mother so far out of my mind because I did not want to accept my connection to that fate. I would see her face in my sisters and fear for them. I did not want to tell them what I saw because I figured they had the same fears I do.

I took up running in my late 20’s and continued through my 30’s. The reason I did so was because it would allow me to assess my lung health regularly and make note of any changes in my lung capacity. I felt if my running times were consistent or improving, it was indicator that I was not going to die of cancer, at least not in the next 4-6 weeks. This is truly the only reason I took it up. I became an avid hiker and would push myself to extreme lengths to convince myself everything was in working order. My mother was not an athlete in any way, so this was another way to differentiate my story, and hopefully it’s ending, from hers. I hoped maybe if I made smart choices, I could stay a few steps ahead of the reaper.

My mother has eight grandchildren she does not know. She would have been the most indulgent and loving grandmother, and I grieve for what these kids all lost-they will never truly know. One of my sisters was too afraid to pass on our horrible legacy and therefore chose not to have children, which is its own kind of loss. I understand why this choice was made. I would have loved to have seen her as a mother, because she is an amazing, loving, kind and wickedly intelligent person.

I am so proud of my sisters. Amanda is an amazing mother of 4 wonderful children, all of whom I treasure. Meg works in cytogenetics-cell science, having conducted cancer testing for a lab. She decided on the field because of the career opportunities, but coincidentally, her knowledge has helped us all to understand the science behind how this could have happened.

MOTHERF*%$#R

On April 4 of this year, my maternal aunt contacted me via text. She seemed to be beating around the bush, probably terrified of sharing what she had learned with me. She told me that recently one of my uncles had been doing some family history research and learned that our grandfather had been stationed at Camp Lejeune sometime from January of 1956-January of 1960. I did not initially understand what the point of all of this was-interesting, but ancient history. She went on to ask if I knew about the contamination in the water there from 1953-1987. I had seen commercials on the television, but obviously had no idea that it had anything to do with my family. I immediately felt the need to validate this information for myself because if true, it changed everything I believed about my life and my mother’s life and the life of the grandparents I barely knew.

The first call I made was to my sister Meg, because I needed to process and attempt to understand this information, and she has always been my sounding board and a huge part of what was left of my support system, plus how could I keep this revelation from her? She and I then contacted Amanda; our youngest sister who was only 13 years old when our mother died. Those were some of the most difficult conversations I have ever had in my life. How do you convey to someone that not only did this suffering not need to happen, but everything we ever believed in our lives was false?

I dedicated my next weeks to extensive research, because I could not believe this was true. I signed up for Ancestry.com, the primo version, which allows one to access military records. What I found validated that my grandfather was a Marine, and I could see from Muster sheets that he was indeed stationed at Camp Lejeune at times, but this was only partial information that did not go far enough to convince me that there was a definitive connection-for example, was my mother born there? I knew she had been born in Teaneck NJ, because it is a piece of information used to validate people’s identity: mother’s maiden name and place of birth.

All of this plunged me into an incredibly acute depressive episode for which I was prescribed additional medications for anxiety and given medical instructions to take a leave of absence from my job. I joined a 10-week grief support group through the CT Hospice. Those weekly meetings saved me during that time, and I will forever be grateful for the facilitators of the group and the participants, who were the best listeners and so understanding and kind. I felt weird joining this group 25 years after my loss, but this was the first time in my life I could fully process what had happened. These folks carried me through some very dark days. My partner, Michael, has been a rock-star for the last three months dealing with my weepy episodes and listening to me talk about my history in a way I was unwilling to share with anyone in the past. He’s probably heard me say “I can’t believe this is real” a thousand times.

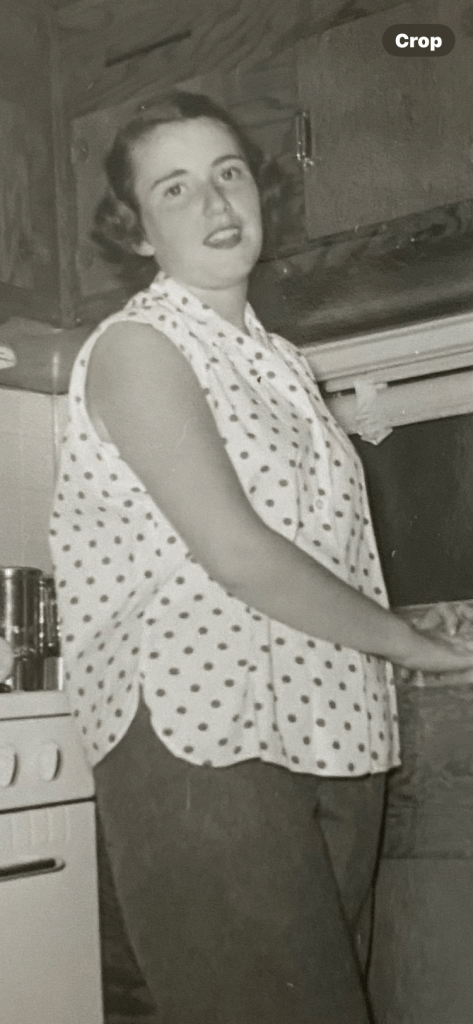

I began looking through old photos and came upon a photo of my grandmother, pregnant, in a trailer home, standing at the sink. For some reason, this image was absolutely devastating. To see this young wife, starting out her family life, so proud of her new home, awaiting the birth of her child, never knowing what the future held-this was so incredibly existentially sad to me. What a bitter realization to process.

I went on about attempting to obtain my grandfather’s service records from the National Archives, which I was able to do because he had died, and the dates of service were more than 60 years ago. I reached out to my Congressional Representative, Rosa DeLauro, and requested that the office help me obtain the records, since I understood it could take a good deal of time to be processed. I truly feel sorry for the poor man who picked up my phone call, trying to convey my request through sobs and gasps. Indeed, they helped me get the records, which arrived at the end of June.

Reconstructing the timeline of my grandparents’ life, I found my grandparents were transferred to Camp Lejeune in August of 1957, and assigned housing in Camp Knox Trailer Park #326. They remained at that address until February of 1959, when my grandfather was sent on an overseas mission to Africa and the Middle East through August of that year. My grandmother had returned to New Jersey to give birth to my mother on January 17, 1959, since her family was there, and my grandfather was leaving shortly thereafter. My grandfather traveled to NJ for my mother’s baptism before shipping out on 2/26/1959. I believe my grandmother chose to give birth in NJ on account of all the baby deaths at Camp Lejeune. Her first child, David, had also died in 1957 while they were in Arlington, stationed at MCHQ, so I imagine she had a healthy amount of fear for the child she was carrying.

This revelation has reframed so many things in my life. I could have had a mother. I could have had grandparents. I could have had the support of a full family. My children could have had grandparents, and support, and an emotionally healthy mother, rather than the barely surviving, beat-up, terrified version of myself that I was able to offer them in my grief. I could have used the support of a family through my divorce, and other difficult times during my life. I will never know what could have been. Would we have all gone to our family home for holidays? I’ve often envisioned myself coming through the door, delicious smells in the air, holiday music playing and being warmly greeted by a family that loved me-don’t we all deserve that?

Would my mother have helped deliver my daughter to college at the University of the Virgin Islands on St. Thomas? St. Thomas was my mother’s favorite place in the world. I remember bringing Maia on a tour there, and sobbing when the plane touched down, thinking about my mother doing that very thing in 1998. Maia and I swam out in Brewer’s Bay to see the sea turtles and I felt so close to my mom as a rainbow filled the sky over the bay. She would have loved that Maia was living there, experiencing the culture, and doing badass things like swimming with dolphins and becoming a scuba diver. I can only imagine her pride. Maia graduated a few years ago, and the idea of taking a trip to her graduation with my mother was a fantasy in my mind. I could almost see her beaming with pride for “our” baby, surrounded by natural beauty and connected by time.

My fears will never go away because they are ingrained in the core of my being. When I realized that I have to continue living, I did not even know what to do with that possibility. I have never entertained a single thought of my old age, retirement, or grandchildren of my own.

My Aunt Charlene suffered a head injury a few years ago for which she was hospitalized in New Hampshire. When we were at the hospital, someone referred to me as her daughter, which brought me to tears and still does because I had not been anyone’s daughter in a very long time. The next time I was able to refer to myself as a daughter was when I was requesting a copy of my mother’s birth and death certificates.

Because of what happened to my mother, I am not the person I could have been. Having the back-up of your family is invaluable. I stayed in my marriage well beyond its shelf-life because of lack of resources and support. My mother raised us to be fierce and independent, determined and brave. Somewhere in all of this, I stopped being fierce and brave and instead lived safely, avoiding risk, knowing my margin for error was zero. I have spent my life afraid of making a single mistake, and beating myself up for my short-comings, never giving myself grace or the opportunity to really live. This is a loss that cannot be quantified.

What makes this so hard to reconcile is that the Marine Corp knew in 1984 about this contamination. They had 15 years of opportunities to reach out to my family between when the contamination was discovered and my mother’s death and 25 years since and have not. There are people that decided we did not deserve to know this information. I saw a hearing wherein a woman stated that it would have been too difficult to locate everyone. This is beyond insulting to the intelligence of most anyone. We know they would be able to locate us if we owed $4.50 in interest to the IRS, so this was deliberate. I can only assume they knew people would disperse and would not be able to tie it back to Camp Lejuene. Someone decided to allow my mother’s health to be impacted, and that her possible illness and death was a reasonable loss if they could save money. They had an opportunity to give her the information, and the opportunity for her to receive screenings in the 15 years before her death. They knew that by only releasing the information locally, most of those impacted would not hear about the contamination at all, ever. I believe the naval hospital on base saw clusters of illness and disease that should have demanded a further investigation, for example all the dead babies and chose to do nothing.

I want to include this bit of information because it enrages me. My mother encouraged her stepson, my stepbrother Mike, to join the military in 1998. He was at a point in his life where he had stopped attending college and was sort of directionless. She told him about the positive things the military had done for her father and about the opportunities he could be afforded. We were all so proud of him when he did enlist in the Army and ultimately became a Green Beret. He changed his name to his Korean name during his service, because he had been adopted. We were incredibly close and wrote so may letters during his deployment to Iraq in 2002-2003. You can look him up-his name was Dae Han Park, and he was killed by an IED on a dusty roadside in Wardak province Afghanistan in March of 2011 after a highly decorated career in the Army Special Forces. I like to think his mother Sharon (who had died in the 90s), and my mother warmly greeted him upon his arrival on the other side, and that he will greet me when the time comes. This was an additional emotional blow and with this current information is even more stinging.

My sisters and I visited our mother’s grave in June this year. The lichen growing on the letters of her gravestone told of the passage of 25 years, and the section of the cemetery is full now. We planted some roses and talked about our grief over the course of our adult lives and how we feel about this not having been as inevitable as we believed. It was during this visit that I realized I had never fully allowed myself to love my sisters the way they deserved all these years. I was afraid of the overwhelming deluge of despondency talking about our shared history could unleash. Plus, I was afraid if I allowed myself to love them fully, I risked another catastrophic loss. What a somber realization.

We’ve committed to using the rest of our time here on Earth to be kinder to ourselves and each other, and to treat each other the way our mother wished for in her final days; to truly be the family we have needed all these years, for ourselves and our children.

I want people to know about this contamination and the Marine Corps handling of it because this could have caused generations of strife within their family, and they may not know. They may still believe early death is a foregone conclusion for them. The Marine Corps has never made any attempts to contact us. We found this out by accident. Who would suggest to their child to join the military knowing that they poisoned Marines and their families and then dodged responsibility for decades, denying rightful claims of disability, and launching PR initiatives full of misinformation? I’ve read the historical reports, all of them, and one thing is clear-there was never any real attempt made by the government to locate us. Those responsible for that decision should be ashamed of themselves, and I hope they will think of my mother on every holiday they spend with their families henceforth.

I want every American to remember one thing: If they can do it to us, they can do it to you, and guess what? They won’t tell you. History shows over and over when polluters have the opportunity to shirk responsibility, they do, nearly 100% of the time. When and if this happens to your family, we hope to have laid the groundwork for more proactive responsibility and accountability. We should be showing the military that we honor their service, not only when actively serving, but when mistakes are made and people die.

Mistakes were most definitively made, and we have the opportunity to finally do right by families like mine that have suffered so much. Admit what was done and stop forcing these elderly veterans and families of the deceased jump through flaming hoops attached to spinning whirligigs atop a minefield to receive justice. It is time.

Thank you for hearing my story,

Jessica Allen

441 Fountain Street

New Haven, CT 06515

j.allen.10045@gmail.com

203-823-3575

Leave a comment